Analysis of phone calls shows how political boundaries could be ideally drawn

By Bill Steele

In an ideal world, political boundaries would enclose groups of people who are connected to each other more than they are connected to outsiders. A new study using a computer algorithm developed at Cornell shows that Great Britain is -- almost -- already organized that way.

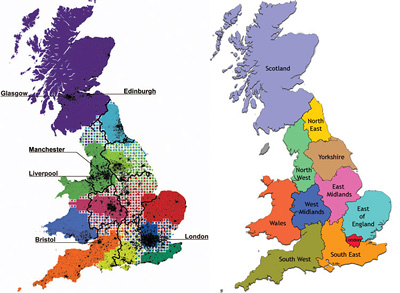

Analyzing a database of British telephone calls, which they call "the largest non-Internet human network," researchers at Cornell, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and in the United Kingdom found that connections coincided remarkably well with administrative boundaries. One surprise was that people in Wales communicate with people beyond their border more than expected. A non-surprise was that Scotland keeps pretty much to itself.

"A community is something where most of the links are inside the community instead of outside," explained Steven Strogatz, the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Applied Mathematics, who advised the researchers on how to analyze the data using an algorithm, or computer method, designed to show how a network breaks down into subsections.

The algorithm was developed by former Cornell researchers Michelle Girvan, now a University of Maryland physics professor, and Mark Newman, now a University of Michigan physics professor. The research is reported in the Dec. 8 issue of the online journal PLoS ONE. The Cornell algorithm is described in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103: 89577-8582 (2006).

"This could be especially useful in regions where there are disputes over where the borders should be. A lot of big databases could be mined to find where people are in terms of human interaction," Strogatz said. "We're not making any claim about what we should do politically; it's to demonstrate the capability."

The methods, he noted, are an extension of classic social science studies of organizations, where researchers observed "who spends time with whom." What's new here is the addition of a geographic overlay, Strogatz said.

The researchers worked with an anonymized database of 12 billion calls over a one-month period, from which they extracted 20.8 million nodes and 85.8 million links between them. They divided the map of the island into 3,042 pixels, each 9.5 kilometers square, and measured the strength of connections -- defined as total call time -- between nodes in each pixel and those in every other pixel. The computer then tested groupings among pixels until it found an arrangement that showed the most links within communities and the fewest between them.

The result coincided nicely with existing boundaries of administrative regions. Communities and political boundaries probably evolved together over many centuries, the researchers suggested, with "cohesive patterns within society promoting change in administrative boundaries and the latter, in turn, affecting human interaction."

One departure from the pattern was that people in eastern Wales communicated extensively with those around nearby cities in the adjacent region of West Midlands. On the other hand, only 23 percent of calls made inside Scotland were to other parts of Britain. "The effects of a possible secession of Wales from Great Britain would be twice as disruptive as that of Scotland," the researchers said.

The study also found a new "region" west of London, around a growing center of high-tech industry -- the British version of Silicon Valley.

The methods used in this research could also be used with cell phone records, which would measure more personal as opposed to business communication, or with credit card transactions or personal travel patterns, the researchers said. "All together, these approaches could lead to a new perspective in regional studies, transportation planning and economic geography," they concluded.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe