Cornell Rewind: The fluid landscapes of yesteryear

By Elaine Engst and Blaine Friedlander

“Cornell Rewind” is a series of columns in the Cornell Chronicle to celebrate the university’s sesquicentennial. The column explored the little-known legends and lore, the mythos and memories that devise Cornell’s history. This installment is the last.

Throughout Cornell’s history, the campus has existed as a fluid representation of history, culture, science, the arts and tradition, which give way to modern mores and contemporary values.

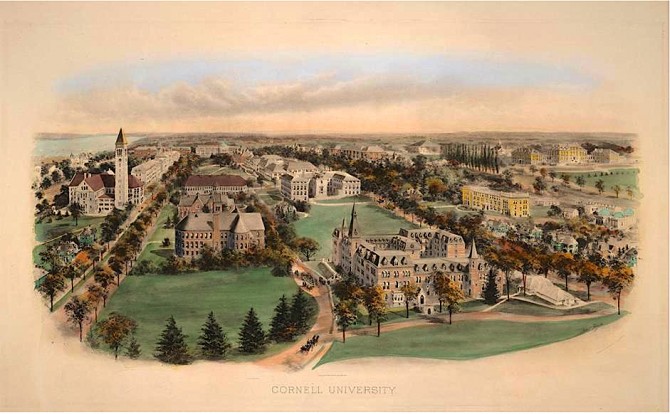

At the start, horses, horse-drawn wagons, students and faculty crossed the muddy campus paths. Today’s grounds are a marvel of infrastructure, energy efficient buildings, curated flowerbeds and manicured lawns. Professor Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen, who taught Northern European languages in Cornell’s early days, wrote a reminiscence article in 1889 in The Cornell Daily Sun, saying, “To [those] who now walk across the university campus, with its stately piles of masonry, its broad elm-shaded avenues and its clusters of pretty [faculty] cottages, it seems scarcely credible that all this is the work of less than 25 years.”

Boyesen continued: “The writer can well remember the time, not so very remote, when the campus was an ungraded, rough-looking hill-top, surmounted by three ugly barracks of gray sandstone. There were no definable sidewalks, and [with] every storm the clay roads were rivers of mud, which no one crossed without dire necessity. It was no unusual thing for the professors to arrive in their classrooms covered with mud from head to foot.”

In Cornell’s 150 years, many buildings have sprung up and – of those – many have changed their mission. The north end of Goldwin Smith Hall was originally the Dairy Building, designed by Charles F. Osborne in 1893. It was the first state-financed facility here. In 1904, the architectural firm Carrere and Hastings incorporated the Dairy Building into their plans for Goldwin Smith Hall. Today, Klarman Hall fits into the footprint of Goldwin Smith.

Cornell built Franklin Hall (1883) to teach electrical engineering. Franklin was renamed Tjaden Hall in 1980, now the home of the Department of Art. Lincoln Hall originally housed civil engineering, but now harmonizes with the Department of Music. Malott Hall once served as the home of the Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management. In 1998, the Johnson School moved to Sage Hall, which originally had served as Cornell’s first women’s residence.

Faculty cottages

Even before Cornell opened, the board of trustees supported the idea of “cottages for professors” on university land. In 1870, they agreed that “lots for professors’ houses be laid out on the university grounds, 100 by 200 feet, to contain about a half-acre each.”

The faculty cottages were substantial houses, as the “lease-lot” arrangement was very advantageous to faculty: The land would cost nothing, and they would pay no taxes. Some faculty took in student lodgers.

Builders completed the house of Willard Fiske, the university librarian, in November 1871, and he became the first faculty member to live on campus. Veterinary professor James Law’s house was finished shortly afterward, but it was in the way of progress – and eventually would be relocated to make way for Rockefeller Hall.

The house of professor Charles Babcock (architecture) – just east of Sage Chapel – was on the western side of today’s Day Hall site. William Henry Miller, who had studied at Cornell, designed homes for Thomas Frederick “Tee Fee” Crane (modern languages), John L. Morris (engineering) and Junius MacMurray (military tactics) along Central Avenue – now Ho Plaza – on the site of Gannett Health Services.

Babcock designed a home in 1880 for professor Bela McKoon, who taught German, and that house became one of the more extravagant faculty cottages along East Avenue. The McKoon house served as a residence for Presidents Charles Kendall Adams and Jacob Gould Schurman, since A.D. White continued to live in his own “President’s House” until his death in 1918. Baker Lab eventually replaced the McCoon House.

At the south edge of Fall Creek Gorge

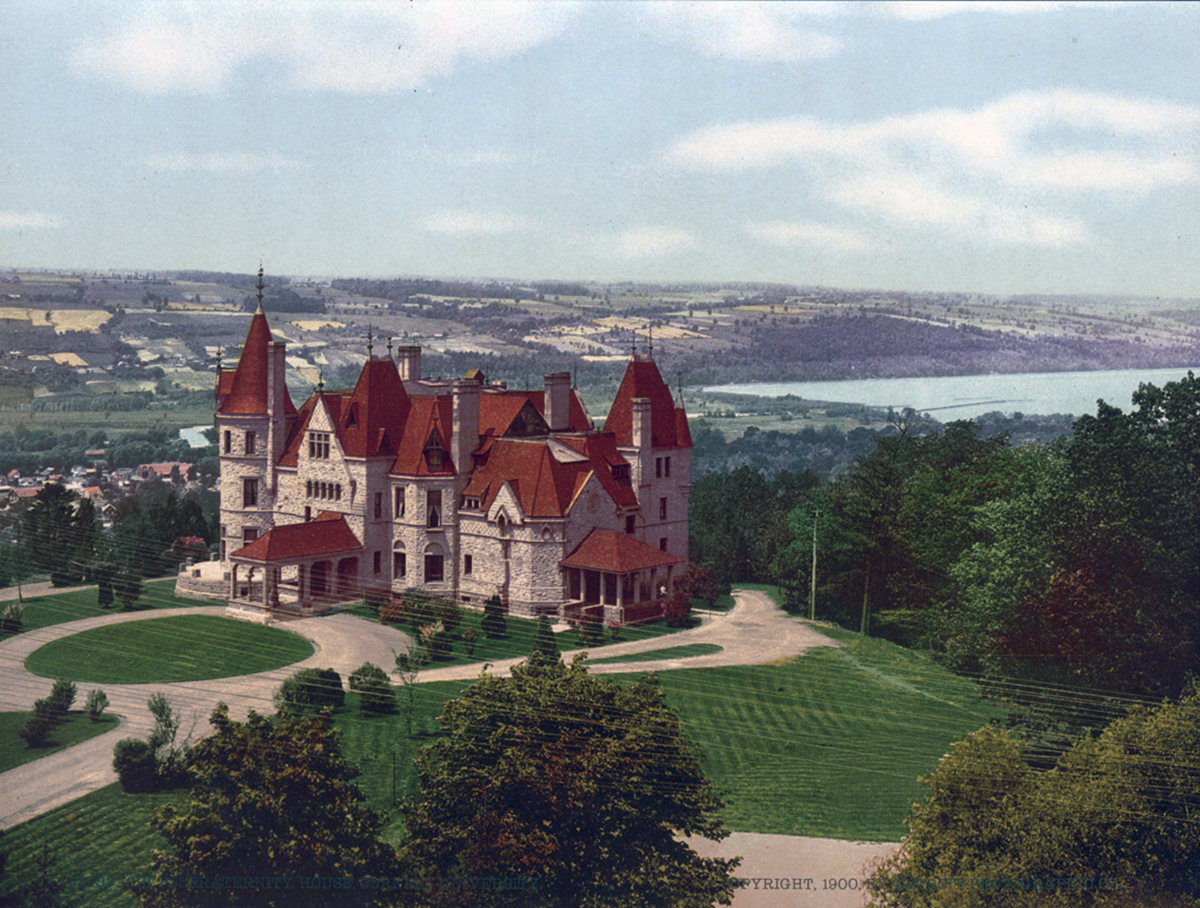

Land that sits along the south edge of Fall Creek Gorge seems historic in any iteration. As the legend goes, Ezra Cornell stood and envisaged an institution for any person seeking instruction in any study near where the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art now stands.

In 1880 heiress Jennie McGraw purchased a parcel along the south edge of Fall Creek Gorge, and Miller designed an elegant villa that became known as the McGraw-Fiske Mansion. McGraw – arguably the wealthiest woman in the United States – married her fiancé, university librarian Willard Fiske, in 1880 on a trip to Europe. Suffering from tuberculosis, she died in Europe in 1881 – never residing in the mansion.

The McGraw-Fiske Mansion sat unoccupied for 15 years, when it was sold to the Chi Psi fraternity, which moved into the dwelling in 1896. The mansion’s elevator was never completed, so the bottom of the elevator shaft was used to store janitorial equipment, including oil rags for the wood floors. On Dec. 7, 1906, the rags caught fire and engulfed the mansion in flames, taking the lives of four students and three Ithaca firemen. The current Chi Psi house occupies the mansion’s original site, on the McGraw parcel.

‘They would have fluorescent lighting’

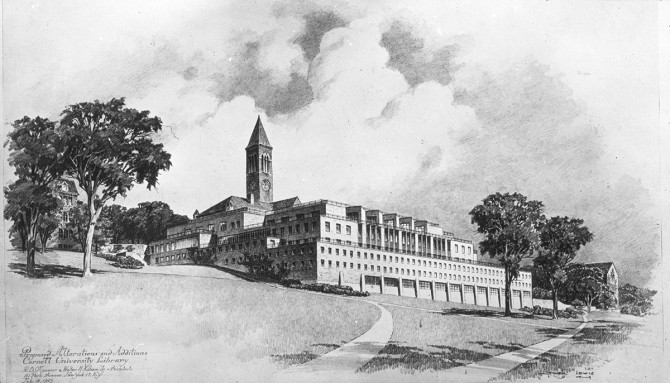

After World War II, the growing campus and main library were squeezed for space. A 1949 Cornell Sun editorial suggested razing the A.D. White House to replace it with a gleaming library. “In such a library Cornellians could smoke, they would have fluorescent lighting less than a hundred feet away, they might have typing cubicles and lounge chairs – which at Harvard have proved to make a more efficient use of space than conventional library equipment. Perhaps most important they could pick their own books from open shelves,” explained the editorial, written by Arnold J. Heidelheimer ’50.

In 1949, the idea of a large edifice – added to Uris Library – and taking over Libe Slope surfaced. A rendering showed a building sprawling over the entire slope. Students, alumni and faculty shot the idea down. While proposals took years to resolve, Boardman Hall, designed by William Henry Miller, was eventually razed in 1958 to make room for Olin Library, which opened in 1961.

Cornell of the future

Cornell’s campus reflects its own personality and values, emboldened to blend the past with modernity. Milstein Hall fuses seamlessly with Sibley; the Human Ecology Building complements Martha Van Rensselaer Hall; and education proceeds in new, unimagined ways. In 2008, the university’s trustee approved a comprehensive 50-year master plan for the campus landscape, physical structure, land use and transportation in Ithaca.

The university continues to grow beyond the Ithaca campus – including at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva, New York, the medical school in Doha, Qatar, and Cornell’s remarkable footprint in Manhattan, particularly Weill Cornell Medicine and Cornell Tech’s campus on Roosevelt Island.

From the campus’s muddy beginnings 150 years ago to the sleek, energy-efficient, LEED-certified buildings of today, the university aims for the future by building on its venerable foundation.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe