Mediterranean diet may protect against Alzheimer’s

By Geri Clark

A Western-style diet triggers changes in the brain that may predispose patients to Alzheimer’s disease decades before they show any sign of cognitive decline, according to new research by Weill Cornell Medicine investigators.

In two studies, published March 23 in BMJ Open and April 16 in Neurology, the investigators showed that diet and insulin resistance directly predicted structural and functional changes in the brain that are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s as early as age 30. The studies found that patients who ate a Mediterranean-style diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and lean protein exhibited fewer Alzheimer’s-related changes to their brains than those who ate a Western-style diet, characterized by high intake of red meat, saturated fats and refined sugar and low intake of fiber. The Alzheimer’s-related changes were worse in patients who also had reduced insulin sensitivity. These findings may help physicians develop prevention strategies for the neurodegenerative disease.

“There is consensus in the scientific community that we might be able to prevent at least one in every three Alzheimer’s cases by addressing lifestyle factors,” said lead author of both studies, Lisa Mosconi, who was recruited to Weill Cornell Medicine as an associate professor of neuroscience in neurology. “Our results point us strongly in the direction that diet should be one of those factors.”

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, affecting 34 million people worldwide. In the absence of effective prevention measures, scientists expect that number to nearly triple by 2050. Alzheimer’s was historically considered as either a natural consequence of old age or genetics, but researchers now know that the changes in the brain that result in Alzheimer’s actually begin in midlife, though patients typically remain asymptomatic into their mid-70s.

“Alzheimer’s doesn’t just turn on when you reach a certain age,” said Mosconi, associate director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian. “Instead, it’s a very long process that starts with changes in the brain when people are in their 40s and 50s. So we have a good 20 years to do something about it. The question is, what can we do in terms of prevention?”

To answer this question, Mosconi and colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine studied 116 patients between 30 and 60 years old who had no cognitive impairment. The investigators used MRI to scan each patient’s brain and took measurements of cortical thickness. The cerebral cortex, or “gray matter,” plays a key role in memory, thought and language. They also collected information about diet, physical and intellectual activity, and vascular risk factors like overweight, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and insulin sensitivity, which are known to play an important role in brain health. “We wanted to address all of these potential causes of Alzheimer’s together,” Mosconi said. “They all influence each other to some degree, but we wanted to tease out how they individually affect the way the brain ages.”

The investigators found in the BMJ Open study that Western diet and insulin resistance directly correlated to reduced cortical thickness, or a lowered brain volume. This is one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. “People who eat a Western-style diet, their brains are literally shrinking, even in middle age,” Mosconi said. “Further, these results accounted for the effects of all other lifestyle factors, indicating that, when people are in their 40s and 50s, diet exerts a stronger influence on Alzheimer’s disease than exercise or intellectual activity do.”

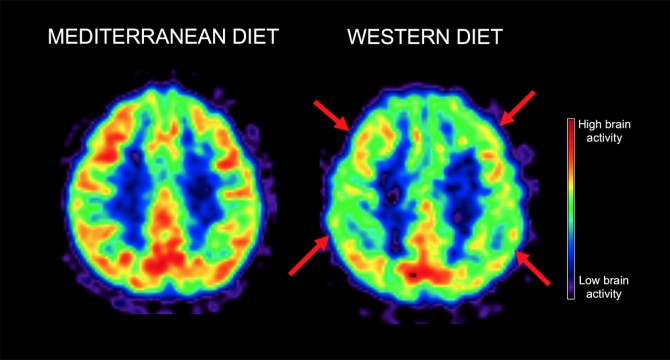

Although brain shrinkage is associated with Alzheimer’s, it is not exclusive to the disease. To further investigate the effect of diet on brain aging, Mosconi and her team examined 70 additional patients whose age ranged from 30 to 60, collecting the same physical, cognitive and lifestyle data. The investigators then divided the group based on those who followed a Mediterranean-style diet – which is already known to be preventative for cardiovascular disease and diabetes – and those on a Western diet. Patients underwent repeated MRI and PET scans of their brains over a period of three years to look at structural changes in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s, as well as the rate at which the brain uses glucose, known as brain metabolism. This biological process is a measure of brain activity; slowed brain metabolism is one predictor of Alzheimer’s disease. The investigators also looked at the emergence and accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques, a major hallmark of Alzheimer’s.

The Neurology study found that patients who ate a Western diet showed a decline in brain metabolism of about 3 percent per year, while brain metabolism remained stable in the Mediterranean diet-adherent cohort. In addition, the Western-diet patients at the start of the study had already accumulated approximately 15 percent more Alzheimer’s-associated plaques in their brains than the Mediterranean group; that number increased about 2 percent per year, while the Mediterranean diet participants showed no change.

Taken together, these results imply that diet could be important in Alzheimer’s prevention, Mosconi said. “This is a highly significant difference. We’re seeing these changes only in parts of the brain specifically affected by Alzheimer’s, and in relatively young people. It all points to the way we eat putting us at risk for Alzheimer’s down the line. If your diet isn’t balanced, you really need to make an effort to fix it, if not for your body, then for your brain.”

Geri Clark is a freelance writer for Weill Cornell Medicine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe