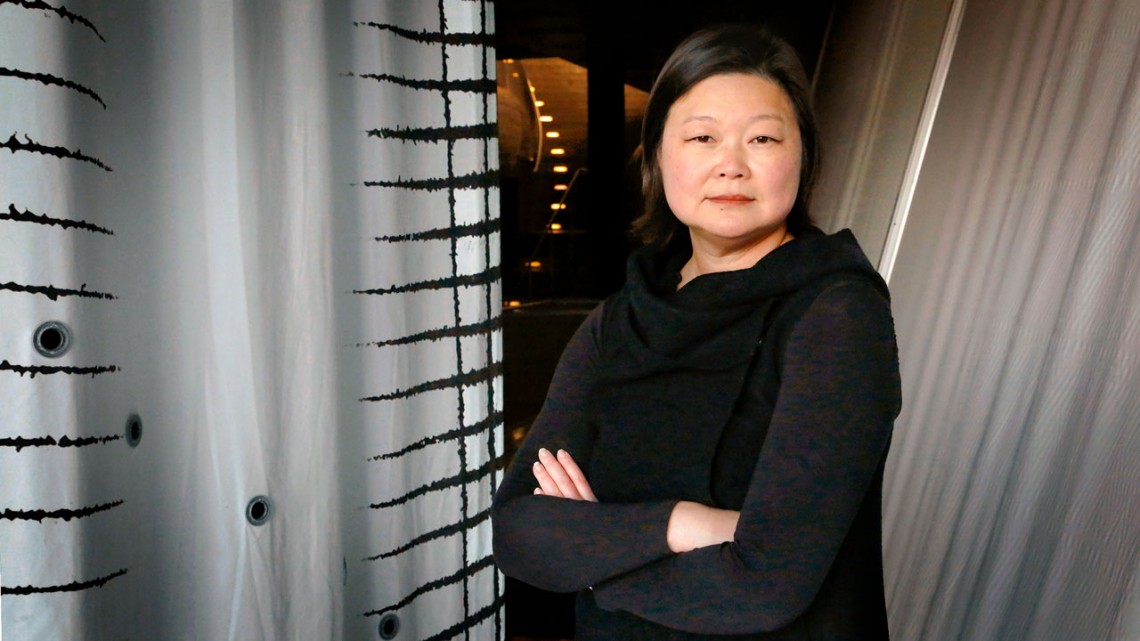

J. Meejin Yoon, B.Arch. ’95, the Gale and Ira Drukier Dean of the College of Architecture, Art and Planning, at Milstein Hall.

New AAP dean sees opportunities for collaboration

By Daniel Aloi

J. Meejin Yoon, B.Arch. ’95, began her term Jan. 1 as the first woman to serve as dean of the College of Architecture, Art and Planning (AAP).

In her return to Cornell, Yoon brings extensive experience as an innovative, award-winning educator and designer. She had taught since 2001 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where she headed the architecture department in the School of Architecture and Planning from 2014 until the announcement of her appointment in July 2018 as the Gale and Ira Drukier Dean of AAP.

Current projects at her independent practice, Höweler + Yoon Architecture LLP – co-founded in Boston with her husband, Eric Höweler, B.Arch. ’94, M.Arch. ’96 – include the Memorial for Enslaved Laborers now being installed at the University of Virginia.

The Chronicle sat down with Yoon in her Sibley Dome office recently to discuss opportunities and challenges for the college and its students and faculty; the evolution of AAP facilities since she was a student; and how architecture, planning and artistic practice engage in critical issues of today.

What opportunities do you see for innovation in AAP’s core disciplines and for strengthening interdisciplinary connections across the university?

What’s amazing about Cornell is the expansive number of disciplines. Design cuts across all disciplines – it is not solely the domain of one field. Where there are more disciplines, there are more possibilities for collaboration and reimagining the way we address challenges in the world.

The three disciplines in AAP belong together, initiating conversations from their different perspectives and different value systems while finding connections within the college and across the university.

Art was part of the architecture department at MIT. I’m really excited to have an art department that has autonomy, that sees visual culture from a very different perspective than architects do – and yet is able to speak a similar language, have resonances and appreciation. I do think artists have a unique way of challenging our assumptions and thinking about the world.

What’s the biggest challenge the college faces right now?

I think the biggest challenge for all of us is to be open to new approaches, and OK with taking that risk and maybe failing. That’s the hardest thing. When you have top-rated programs, it’s hard to make an argument for why one needs to take a leap of faith, or take on a new initiative or a new way of working.

The goal is not to be ranked No. 1 – it’s simply an outcome of a great college. The goal is always to produce excellent architects, excellent artists, excellent planners – to be the most relevant, lead critical conversations, and engage in creative work, scholarship and research that will have an impact.

What do you think will be the most significant change or challenge for students in the near future?

I think it has to do with a sense of empowerment about one’s own future. Because our students have grown up in an age of disruptive technologies, they’ve seen large shifts happen within a very short time. In a way, it should feel to them like anything is possible – that you can develop a good idea and turn it into a successful startup. But I feel they’ve seen it happen exclusively through tech and finance. They may have amazing ideas that will contribute and help transform our built environment or social context, but there are fewer precedents in their young adult lives to see how that can happen – in the nonprofit sector, for example.

Also there’s a challenge in trying to shift a sense of temporality – how do you initiate something that you can stay invested in for a significant duration of time? I think that historically art, planning and architecture all share that distinction as a lifelong disciplinary pursuit, but it’s getting more challenging for students to see how these disciplines can have an impact in the short and medium term. I think it’s harder because the startup generation created tech companies that now are established mega-companies. I think we need to celebrate diversity and multiplicity – small- and medium-scale contributions are essential. And I think that optimism in the agency of our disciplines is hard but more important than ever to have in a context like today.

This speaks to inspiring students to effect change now and as professionals. How can training in architecture, art and planning best engage with critical issues?

Resilience and natural resources: For planning and architecture, it would be to facilitate opportunities for collaborative workshops that are problem-based and look at things like post-disaster housing, sea level rise, ecology and sustainability.

When architects and planners are separated, the work naturally gravitates toward their set of values. Intersecting more perspectives and value systems is extremely helpful to understand, for example: What are the limits of the federal government or the limits of the nonprofit sector? What are the limits of and gaps in our disciplines, and can we help bridge those gaps?

Urbanization: The world is more than 50 percent urbanized, and cities keep growing. There’s the accumulation of wealth and opportunity and culture in many of these growing urban contexts, and they’re growing at such a fast rate, compounding challenges of mobility and sustainability and health. I believe that urbanization is the biggest challenge of our time, not just in terms of pure management but understood in terms of regional and global impact, because certain successes in the urban context draw resources, populations and talent out of other areas.

Urbanization is something our faculty and students have a greater understanding of because their context includes the regional and the global. You cannot understand urbanization and its potentials and its impact on larger contexts without seeing it from a regional science and data science perspective.

Disparity: I think art calls into question many socio-economic conditions today. That’s important; art can ask those really hard questions, and critical art practices do this. Planning has great mechanisms by which, through the study of policy and development, it can address issues of disparity. In architecture, I think the studios help students understand the complexity of the built environment, the importance of context and the challenges to the environment and resources.

Technological change: The changes in technology that have affected architecture, art and planning – to improve information available for research, open up design possibility, facilitate coordination and help manage complexity – have been for the most part positive, and have been embraced organically.

The technological challenges today are in two areas: One is our level of trust, not of the technology itself, but what is being communicated through that technology and how it is being used. Basically, students have to become more discerning about their access to information.

The second is automation – not only robotic and manufacturing-based, but also artificial intelligence. This will impact labor, planning and design. It’s not that I’m afraid these things will replace the architect, planner or artist; it just means there will be opportunities to do things differently.

Because architecture is tied to construction, we’re going to see automation and construction have an interesting intersection when we think about labor. I think it will make construction safer, but it will also impact craft, skill and areas the built environment has always treasured.

AAP’s physical presence has changed a great deal in the 25 years since you were a student. What’s your impression of Milstein Hall?

I think it’s great to have studio all on one floor; having a horizontal landscape of studio production is incredible. It is an important building of contemporary architecture, and it being located among Cornell’s more historic buildings is also significant. It shows that architecture changes over time – the technologies change, the materials change, the performance metrics change, the aesthetics change. I like that there is a diverse range of buildings for one college – Tjaden, Sibley, Rand and Milstein … and the Foundry.

What about the AAP NYC program, now at 26 Broadway (the Standard Oil Building)?

Its location is interesting. You can’t sit in that historically important building and not feel like you are at the tip of Manhattan.

I think it’s important that AAP has a constant presence in the city; many of our alumni are in New York City. It’s a place where you feel energy and you encounter the city and the buildings and the art scene all intensely together. And you know there that you can have a way to contribute, a way to have impact. You feel the agency of the physical and built environment with more intensity.

Equally important to our pedagogy is our footprint in Rome, where we not only engage in matters of antiquity but also explore the present and future of a global society.

And the design of the Mui Ho Fine Arts Library, opening in Rand Hall later this year?

It’s dramatic, both in design and purpose. At a time when everyone is going to non-book formats and all that has happened in publishing and technology, libraries have become more and more important as social and cultural spaces. I like that in the new Fine Arts Library there is both the physical presence of information as well as an embrace of digital technology, online information and access to knowledge.

What is going to be amazing about the new library is to have a space that is large enough to host students from our college and across the campus to be with books – to understand that there is a material presence of knowledge and knowledge production as well. To understand they are not there to just look for the books, they’re there to create and produce new knowledge – new books.

I know that library is going to be important for AAP. I have many fond memories of the studios that were previously in Rand Hall. Rand was known as this 24/7 kind of space, lights are always on, you’ll always see someone in there. I think the library, as a program, will also have that same kind of quality, that it’s an active, public-use space. And I love that it’s right above the fabrication shops, having two forms of production stacked right on top of each other. One could argue they’re both about making research tangible and accessible. Making is as much about research and research is just as much about making – making knowledge, formats, new worlds.

How would you define yourself, outside of your job as dean?

I define myself as a designer; I’m always trying to see patterns, to see relationships, to see the way things work, or don’t work.

What I enjoy about being a designer is, in every context you learn about an area you just were not knowledgeable about before. You have an opportunity to become an expert on a topic, or expert enough, to contribute from your disciplinary perspective. That is really fulfilling. And I think that’s why I’m here, to be back in a context that pushes me to keep learning.

Architecture has always been my job and my hobby. But I am also a mother; I have an amazing 8-year-old daughter, Kaya. My husband, Eric Höweler, is my design partner, so I don’t escape architecture or design. And my daughter doesn’t, either.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe