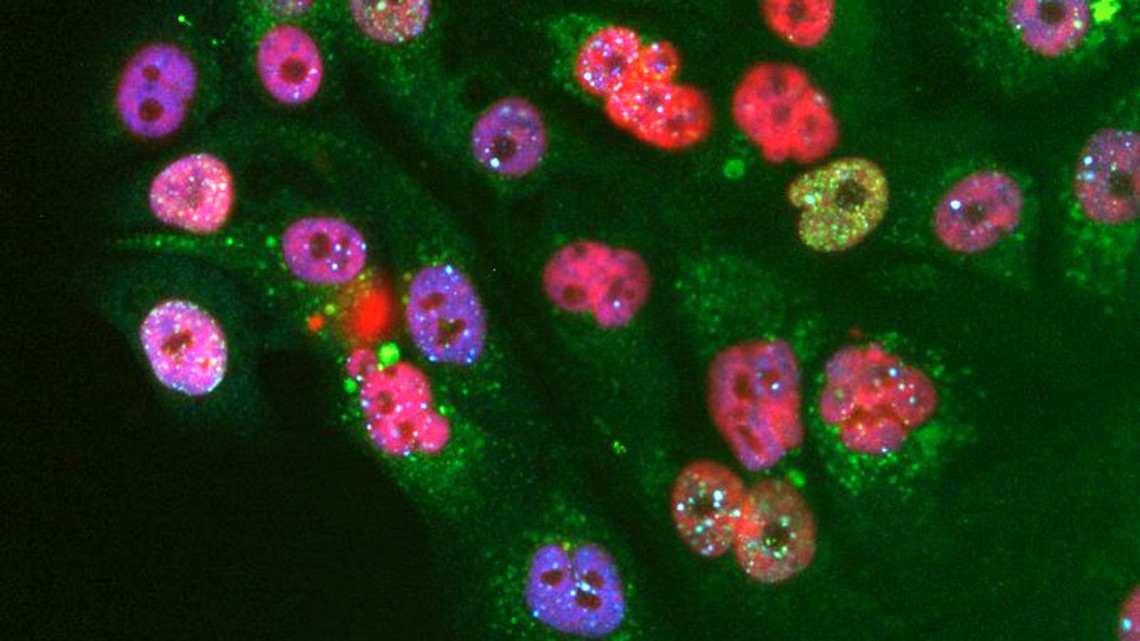

Pancreatic cancer cells showing signs of DNA damage (bright white and green dots) after treatment with chemotherapeutic drug taxol followed by CDK4/6 inhibitors.

New chemo combo shows promise versus pancreatic cancer

By Heather Lindsey

The targeted drug palbociclib may boost the effectiveness of chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer if the two treatments are given in the right sequence, according to new preclinical research by Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian investigators.

The study, published Feb. 27 in Cancer Cell, found that palbociclib may stop pancreatic cancer cells from repairing DNA damage caused by chemotherapy; that DNA damage is what causes the cancer cells to die. This result suggests that chemotherapy drugs used for pancreatic cancer, such as paclitaxel, should be given first, followed by palbociclib.

“The goal is to one day give less chemotherapy and to make the chemotherapy we do give more effective,” said co-senior author Dr. Manuel Hidalgo, chief of the Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

About 57,600 people in the United States will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2020, according to the American Cancer Society, and about 9% of these individuals will be alive five years after the cancer is found.

While chemotherapy drugs – many of which work by destroying the DNA in cells – are part of the standard of care, researchers are looking for new medications to add to the drug treatment arsenal. Scientists have been interested in the potential of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors like pablociclib, which are already approved for metastatic breast cancer, to improve outcomes in pancreatic cancer treatment. These drugs block the enzymes CDK 4 and CDK 6, which are important for cell division, a hallmark of tumor malignancy.

Scientists initially found that using CDK 4/6 inhibitors at the same time as chemotherapy made pancreatic tumors more resistant to chemotherapy, Hidalgo said. The inhibitors prevented cancer cells from entering a phase of the cell cycle in which DNA replicates and becomes vulnerable to damage from chemotherapy drugs.

In the new study, researchers found that the sequence in which these drugs are given is critical. Hidalgo and his colleagues studied the activity of the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel and palbociclib in mice with human pancreatic tumors and in mice with genetic mutations found in pancreatic cancer.

The scientists discovered that giving paclitaxel first and palbociclib second reduced pancreatic cancer cell growth. In contrast, giving the mice palbociclib first and paclitaxel second caused the chemotherapy to destroy fewer cancer cells.

Hidalgo and his colleagues found that giving palbociclib after chemotherapy essentially gave tumors a 1-2 punch.

“Oftentimes you hit tumors with chemotherapy, and some cancer cells die, but other cancer cells find a way to recover,” said Hidalgo, who’s also a senior member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine. Palbociclib, he said, prevents the recovery process by interfering with several DNA repair mechanisms.

The study was partially funded by Pfizer Inc., and conducted with researchers from Pfizer and the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO). Hidalgo has consulted, received honoraria and has an equity stake in Champions Oncology and PharmaCyte Biotech; has been a paid consultant and received honoraria from Pfizer; served on the scientific advisory board and has an equity stake in Agenus; and has served on the scientific advisory board for InxMed.

Heather Lindsey is a freelance writer for Weill Cornell Medicine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe