A collaboration led by Lawrence Bonassar, the Daljit S. and Elaine Sarkaria Professor in Biomedical Engineering, proposes a new two-step technique to repair herniated discs.

Two-step method patches herniated discs

By David Nutt

Anyone who has tried to repair a flat tire knows it’s not enough to re-inflate the tire. The tire also needs to be soundly patched.

A similar principle applies to treating herniated discs. After a rupture, a jelly-like material leaks out of the disc, causing inflammation and pain. The injury is usually treated one of two ways: A surgeon sews up the hole, leaving the disc deflated; or the disc is refilled with a replacement material, which doesn’t prevent repeat leakages. Each approach on its own isn’t always effective.

A collaboration led by Lawrence Bonassar, the Daljit S. and Elaine Sarkaria Professor in Biomedical Engineering and in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, combined these methods into a new two-step technique. This approach uses hyaluronic acid gel to replace the leaked material and a collagen gel to seal the hole, resulting in a “patched” disc that maintains mechanical function and won’t collapse or deteriorate.

The team’s paper, “Combined Nucleus Pulposus Augmentation and Annulus Fibrosus Repair Prevents Acute Intervertebral Disc Degeneration after Discectomy,” published March 11 in Science Translational Medicine.

“This is really a new avenue and a whole new approach to treating people who have herniated discs,” Bonassar said. “We now have potentially a new option for them, other than walking around with a big hole in their intervertebral disc and hoping that it doesn’t re-herniate or continue to degenerate. And we can fully restore the mechanical competence of the disc.”

Tens of millions of people in the U.S. experience back pain resulting from damage to the vertebrae or intervertebral discs. These discs are composed of essentially two parts: a stiff tissue on the outside called the annulus fibrosis; and a softer, gelatinous material in the center, the nucleus pulposus, that keeps the disc pressurized and able to hold its shape and height during physical movement.

If the outer layer ruptures, the jelly-like nucleus pulposus leaks out and comes into contact with the nerve root or spinal cord, inflaming it. Extracting the leaked material won’t stop the disc from continuing to degenerate, nor will it restore mechanical function. Suturing the hole shut is a challenge because the annulus fibrosis has no blood vessels, and without them it doesn’t heal very well. Removing the disc entirely and fusing the adjacent discs together may relieve the pain, but can result in limited mobility.

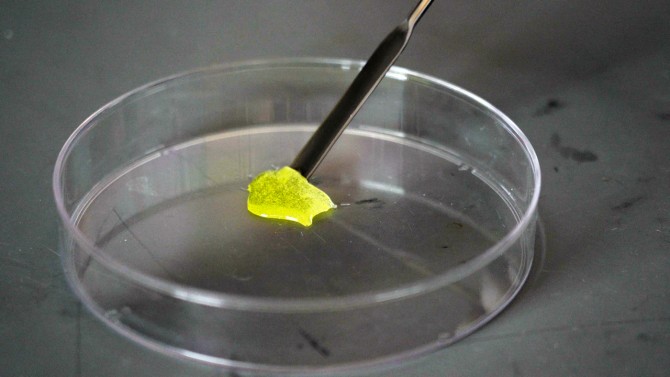

Bonassar’s research group seeks engineering-based solutions for degenerative disc disease. Over the last decade, the group has developed a collagen gel that incorporates riboflavin, a photoactive vitamin B derivative. Instead of sewing up a ruptured disc, the researchers can patch it by applying their gel and shining light on it to activate the riboflavin.

The resulting chemical reaction causes fibers in the collagen to bond together, and the thick gel stiffens into a solid. Most importantly, the gel provides a more fertile ground for cells to grow new tissue, sealing the defect better than any suture could.

To keep the disc pressurized and mechanically functional, Bonassar worked with Fidia Farmaceutici, an Italian pharmaceutical company that manufactures a hyaluronic acid gel used in Europe.

“The idea is, if you have a herniation and you’ve lost some material from the nucleus, now we can re-inflate the disc with this hyaluronic acid gel and put the collagen cross-linking seal on the outside. Now we’ve refilled the tire and sealed it,” Bonassar said. “What the paper shows is that both of those things are critical.”

Bonassar’s other collaborator, Dr. Roger Härtl, a neurosurgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, used the two-part technique to repair lumbar discs in sheep. The team found the technique successfully healed the damage to the annulus fibrosus, restored disc height and maintained mechanical performance of the spine, up to six weeks after injury.

The technique only takes five or 10 minutes and can be applied in conjuction with a discectomy, the hourlong procedure by which the leaked nucleus pulposus is removed from the nerve root. The technique could be used to address other types of disc degeneration, or integrated into other spinal procedures and therapies.

“The beauty of this is it’s a relatively simple application of the technology,” Bonassar said. “We hand the surgeon a needle, they inject it. Here’s this other needle and they inject it. Then shine a light; OK, you’re done.”

The paper’s lead authors are doctoral student Stephen Sloan and Christoph Wipplinger, a research fellow with Dr. Härtl. Other contributors included doctoral student Duncan McCloskey; Rodrigo Navarro-Ramirez and Sertaç Kirnaz, both research fellows with Dr. Härtl; neurosurgical resident Franziska Schmidt, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital; and researchers from Fidia Farmaceutici and the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York.

The research was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Center, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; and the Colin MacDonald Fund.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe