Research suggests how tumors become aggressive prostate cancer

By Julie Grisham

The genetic changes that underlie an especially lethal type of prostate cancer have been revealed in a new study by investigators at Weill Cornell Medicine. Learning more about what causes this type of cancer, called neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC), could lead to new approaches for treating it.

Most early stage prostate cancers require male hormones (androgens) like testosterone to grow. However, as they advance, they may evolve into castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), a type that can grow without hormones and is harder to treat. NEPC is one type of CRPC.

The findings, published June 7 in Nature Communications, revealed important findings about the basic biological actions that lead to this cancer. Dr. Nicholas Brady, an instructor in pathology and laboratory medicine, and Alyssa Bagadion, a Weill Cornell Graduate School doctoral student in the Rickman lab at the time of the study, are co-first authors on the study.

“Prostate cancer is a hormone-based cancer, so many men are given hormone therapy to block the signaling that drives the cancer,” said senior author Dr. David S. Rickman, an associate professor of research in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine.

“However, some prostate cancers figure out how to lose their androgen receptor,” Rickman said. “They shed their dependence on androgen signaling and turn on molecular programming that allows them to grow and metastasize in the presence of androgen receptor inhibition. NEPC is particularly good at this.”

Ten years ago, research in Rickman’s lab revealed that a gene called MYCN gets turned on during the time some prostate cancer cells are developing resistance to hormone therapy. The gene codes for a protein called a transcription factor, which regulates which genes get turned on and turned off by binding to DNA. The new study builds on this work.

Previous analysis had shown that loss of another gene, called RB1, is also common in NEPC and other forms of CRPC. The investigators decided to study the relationship between the two genes. They started by examining tumor tissue from 76 patient biopsies; 55 of the samples were classified as CRPC and 21 were classified as NEPC. They then looked at the genetic changes in the samples.

“We found that patients with CRPC or NEPC tumors that harbored both MYCN overexpression and RB1 genomic loss had a worse prognosis compared to those with only one of these alterations or neither alteration,” Rickman said. “This suggested a synergistic role between these two genes that had never been described before.”

The researchers then studied this same combination of gene alterations in mouse models of prostate cancer. They found that within two or three months, the mice harboring both of these alterations together, along with loss of a tumor suppressor called Pten, developed large, invasive androgen receptor-negative tumors that look very much like the tumors found in patients with NEPC. The mice also developed metastases in the same organs that patients do, including the lungs and the liver.

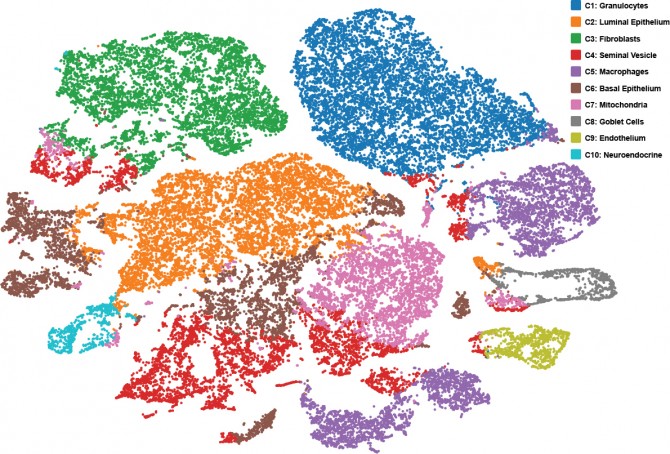

“We decided to take a molecular deep dive into the tumors that came from these mice,” Rickman said. One thing the investigators found was that the tumors were very heterogeneous, with several distinct subpopulations of cells. Another major finding was that the mouse NEPC tumor cells harbored clinically relevant epigenomic changes (e.g., DNA methylation). This type of change alters the way that DNA is transcribed into RNA. The analysis also allowed them to characterize in more detail the mechanisms by which MYCN and RB1 acted on each other to drive the progression to more aggressive cancer cells.

“This research, including our data on single cells and the characterization of heterogeneity, can now be mined to identify potential new therapeutic targets,” Rickman said. “We want to find a way to treat these tumors and stop the progression, before they actually get to this lethal form of prostate cancer.”

This approach could include both new drugs and existing drugs, he said, including those that target some of the epigenomic changes seen in NEPC.

One next step for the research is to go back to the clinical samples to identify markers that are associated with this tumor progression. These markers could be used to predict which patients are most likely to develop NEPC.

This research has implications for other kinds of cancers in addition to NEPC. In particular, overexpression of other members of the MYC gene family combined with the loss of RB1 has been implicated in small cell lung cancer, another aggressive tumor type that currently has few good treatments. Additionally, the findings could be applied to the pediatric neurological tumors neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma, where MYC genes also play an important role.

Julie Grisham is a freelance writer for Weill Cornell Medicine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe