Cornell University Cooperative Extension (CUCE) staff support New York City residents through their longstanding community relationships and their expertise informed by Cornell research. In this photo, CUCE urban agriculture specialists Yolanda Gonzalez, left, and Sam Anderson, center, consult with farmers at Randall’s Island Urban Farm.

Cooperative Extension in NYC: ‘Uniquely suited to help’

By E.C. Barrett

To help boost COVID-19 vaccinations, Cornell University Cooperative Extension educators are meeting New Yorkers where they are – whether that means church congregations, neighborhood listservs or parking lots where undocumented day laborers gather to find work.

“There will be hundreds of people at these parking lot locations waiting for someone to come by and hire them, interacting with each other, and many of them live together in tight quarters,” says Carol Parker, Cornell University Cooperative Extension-New York City (CUCE-NYC) program leader for nutrition and health. “The potential for infection is absurd and we go there and find that no one has reached out to them. So we’re doing some of that legwork and outreach, because we have to get everyone vaccinated.”

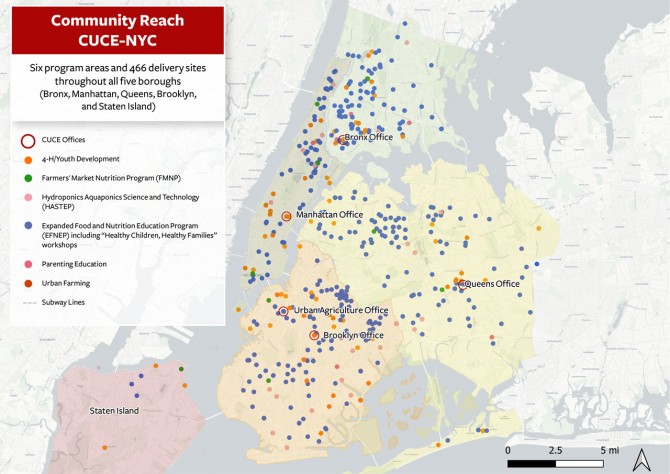

These vaccination efforts are one of the countless ways CUCE-NYC supports residents of every borough in New York City, thanks to its longstanding community relationships and informed by research and expertise from the College of Human Ecology (CHE) and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS). COVID-19 has made these programs even more vital, with CUCE-NYC programs and partnerships not only operating vaccine clinics for underserved populations but also helping parents care for children and teaching kids about fitness and nutrition.

The New York City programs, housed within the Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research, are part of the statewide Cornell Cooperative Extension, which connects communities in every county with Cornell research. An integral part of Cornell’s land-grant mission, faculty and staff – primarily from CALS and CHE – collaborate with extension staff, government agencies, partners and volunteers in order to improve people’s lives.

“We bring the hands-on learning and evidence-based curricula developed by Cornell researchers to our understanding of the people we’re working with, and adapt those projects based on their needs,” says Jackie Davis-Manigaulte ’72, senior extention associate and program leader for CUCE-NYC’s family and youth development initiatives. “And we share with faculty and researchers what we see in our work on the ground and help conceptualize approaches for addressing needs, so the information pipeline flows both ways.”

Mobilizing resources for vaccinations

New York City’s neighborhoods are some of the hardest hit by COVID-19 nationwide. Vaccination efforts in these communities have been hampered by myriad factors, from a lack of technological resources and access to information to mistrust based on historical medical abuses, and fears stemming from immigration status.

“In settings where vaccine hesitancy affects people’s trust, working with faith-based organizations is a proven strategy to help overcome barriers,” Parker said. “We’re connecting with traditional and nontraditional faith-based organizations, going into small storefront churches and doing tremendous outreach with those congregations, talking to them about the science and helping them schedule appointments.”

Parker said CUCE-NYC trained educators are also speaking with their communities and classes about vaccination. At one pop-up clinic, a single nutrition educator was responsible for 40 people showing up to get the jab after she reached out through her block association listserv.

An initial round of partnership-led community pop-up vaccination sites was so successful they were quickly scaled up in collaboration with the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The model is now informing a two-year project to boost vaccine confidence, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and drawing on the expertise of CCE in Suffolk and Delaware counties, the Cornell Farmworker Program, and Neil Lewis Jr., assistant professor of communication in CALS.

“We are uniquely suited to help with this problem because we are planted in these communities,” Parker said. “We’ve been around a long time and there is a level of trust … that comes from decades of working to improve the health and well-being of the communities we serve.”

Twofold benefits

Brendon Choy was in ninth grade when he started partipating in CUCE-NYC’s Choose Health Action Teens (CHAT) program, developed by Wendy Wolfe, research associate in Cornell’s Division of Nutritional Sciences, in collaboration with CUCE-NYC.

In CHAT, teens are trained to teach the Choose Health: Fun, Food, Fitness curriculum to children 8-12 years old. The award-winning, hands-on curriculum, also developed by Wolfe, encourages the behaviors that Cornell research has shown prevent excess weight gain and chronic diseases.

Now a pre-med senior at Columbia University, Choy says the CHAT program was an empowering experience – and gave him invaluable professional development.

“I do science research, which requires a lot of going out beyond the bench to present your research to people,” Choy says. “The communication skills I gained in CHAT directly apply to being able to speak about and explain complicated science topics to different people. It’s kind of like explaining why breakfast is important to elementary school kids. It’s about being able to break down complex things into much simpler terms for different audiences to understand.”

Wolfe said CHAT program benefits teens in two ways.

“You’ve probably heard the quote ‘The best way to learn something is to teach it,’” Wolfe says. “They’re not only learning the content, they’re also being role models for these younger kids and they’re being put in positions of responsibility, which seems to motivate them.”

When COVID-19 threatened to put CHAT on hold for summer 2020, a team including Choy, Davis-Manigaulte, Wolfe and their students converted their class to an online format and organized the delivery of supplies such as mixing bowls, measuring cups and fresh produce to the homes of the kids in the program.

Supporting parents and families

Alfonso Damien’s wife signed him up for parenting classes at CUCE-NYC to help him manage his emotions. In the first workshop Damien attended, six years ago, Luis Almeyda, extension support specialist and parenting education program coordinator, sent home the seven participating fathers with a list of questions to ask their children, including “Who is your hero?”

When Damien’s daughter responded that he was her hero, he broke down crying.

“If she’s looking at me like a hero, why do I act like I do?” Damien recalled asking himself. “When I went back to class I remember all of the fathers were crying. I started asking myself all kinds of questions. I was born in Mexico. I was taught men don’t cry. I was taught you have the right to ask your wife to do anything.”

Damien says the parenting program changed his life.

“Almeyda got me to question all of it. Sometimes it makes me feel backed up against a wall, not wanting to ask these questions,” Damien says, “but I do, because I want to do better for my wife and children.”

Almeyda has facilitated workshops for 28 years, reaching around 250 parents a year, with some participants continuing to attend for years as their children grow and new challenges arise.

Working with public and charter schools, Almeyda is often invited to run workshops for parents who have reached a crisis point with their child or who struggle to relate to their child. The majority of parents are Spanish-speaking, and around half are undocumented immigrants, with low incomes and low literacy levels. Many are living in apartments with one or two other families – challenging parenting conditions even without COVID-19 lockdowns.

Almeyda said parents are usually repeating the parenting they experienced growing up. Before they can integrate new parenting skills, they first have to break down how they were raised and how it made them feel. Discipline, he’s learned, is often a deeply held belief that parents begin to question.

“Parents tend to go into these sessions looking for a formula that will make their children obey them, but we know that’s not how it works,” he said. “So that’s one of the things we talk about, moving from thinking about discipline as control to having a relationship with their child that is about helping them develop in healthy ways.”

Curious learners, future leaders

Kyra-Lee Harry knew in middle school that she loved math and science. “But I didn’t know what I could do with it, aside from being a doctor,” Harry says.

She credits 4-H and the annual statewide Career Explorations Conference – held at Cornell for the last 90 years – with broadening her understanding of how she could leverage her natural talents and interests.

“The Cornell conference was the first time I was introduced to the field of engineering as a discipline,” Harry says, “and I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

Each year around 500 4-H members and chaperones attend the three-day CareerEx event, aimed at providing an immersive exploration of future education, career opportunities and campus life through workshops led by Cornell faculty and graduate students.

Harry had joined 4-H in sixth grade and started a new club when she moved to Medgar Evers College Preparatory High School in Brooklyn. In addition to introducing her to new areas of study, 4-H gave her many opportunities to grow her other passions of public speaking and civic engagement. In 2018, she was chosen as one of four nationwide recipients of 4-H’s highest honor, the National Youth in Action Pillar Award, for her civic engagement work. In 2021, she graduated from New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering.

“4-H has been a vital part of my life,” Harry says, “from national opportunities, to the mentorship of 4-H leaders who have kept in touch with me throughout my life, and my community of peers.”

CUCE-NYC’s 4-H youth development programs also offer kids ages 8-19 informal learning opportunities in STEM, nutrition and health, leadership development and civic engagement.

For example, the 2020 4-H STEM Challenge, Mars Base Camp, offered 8-14 year-olds the chance to explore various aspects of sending a mission to Mars, while learning mechanical engineering, computer science, physics and agriculture.

Even with a decrease in participation due to COVID-19, 4-H had 4,360 youth take part during its most recent complete program year.

“They can take chances, try something new and stumble a little bit or a lot, without negatively impacting their academic outlook,” says Lucinda Randolph-Benjamin, CCE’s 4-H program leader. “A 4-H program will introduce you to something you never would have thought of, and that can change the possibilities you imagined for yourself.”

E.C. Barrett is a freelance writer for the College of Human Ecology.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe