Professor Antonio DiTommaso, pictured here at the Cornell Weed Science Teaching Garden, first encountered the classic identification guide “Weeds of the Northeast” when he was an undergraduate student in Canada. Now he is a co-author of the book’s second edition, along with former Cornell faculty members Joseph DiTomaso and Joseph Neal, and Richard Uva, MPS ’94, Ph.D. ’03.

Unlikely coincidence blooms as classic weed guide gets updated

By David Nutt, Cornell Chronicle

The wild parsnip is finally getting its due.

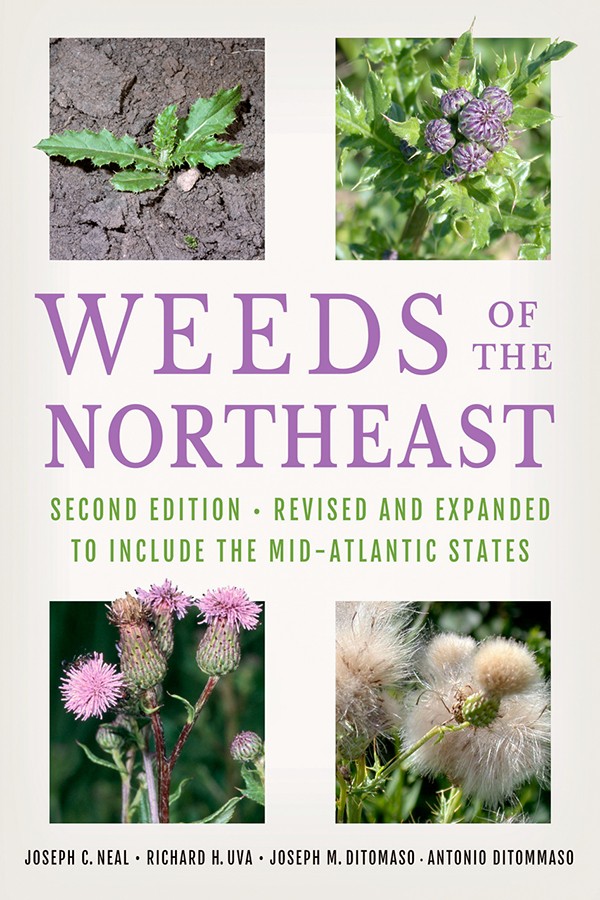

When “Weeds of the Northeast,” a comprehensive identification guide authored by a trio of Cornell researchers, was first published by Cornell University Press in 1997 it quickly became a classic of the field – and for the field – helping legions of botanists, home gardeners, green thumbs, landscape managers, pest control specialists and allergists spot invasive plant life across the region.

Over the last 25 years, the book sold nearly 100,000 copies, making it one of the press’s top sellers. But times change, and so does the flora. In March, CUP published a second edition of “Weeds of the Northeast” that adds more than 200 new species – such as waterhemp, Japanese stiltgrass and garlic mustard – that have been slowly encroaching into the Northeast, as well as various weeds that, for one reason or another, were omitted from the first guide (apologies to the wild parsnip). The book also updates terminology and expands its footprint to include more species from the mid-Atlantic states and upper Midwest.

The creation of the new edition hinges upon an extraordinary coincidence. You could call it a tale of two DiTommasos. Or, more accurately, a DiTommaso and a DiTomaso.

The original “Weeds of the Northeast” took root as the master’s thesis of Richard Uva, MPS ’94, Ph.D. ’03, who developed the manuscript with a pair of faculty members in the Department of Horticulture and the Department of Crop, Soil and Atmospheric Sciences (now the School of Integrative Plant Science Horticulture Section and Soil and Crop Sciences Section) in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences: associate professor Joseph Neal and weed science professor Joseph DiTomaso.

After the book was published, the team scattered. Uva eventually settled in Maryland, where he is co-owner of Seaberry Farm. Neal went to North Carolina State University.

DiTomaso left Cornell for the University of California, Davis, and his exit was followed by the arrival, in 1999, of a weed scientist from McGill University in Montreal named, improbably enough, Antonio DiTommaso – an event that caused confusion for pretty much everyone.

“When I got to Cornell, students taking my class were all like, ‘Dr. DiTommaso, I love your book.’ I knew what they were talking about. I said, ‘I’m not that guy,’” said DiTommaso, who is now professor and chair in soil and crop sciences at SIPS. “What are the chances that two people with this last name of Italian origin would be in weed science, in the same department, teaching this course? It’s insane.”

The coincidence has become something of a legend in the North American weed science community.

“We’ve had postdocs that have been in both of our labs,” DiTommaso said. “They would always say something like ‘I survived both these guys.’”

Roughly five years ago, the original researchers decided it might be time to update the book to correct oversights, modernize terminology and incorporate new species that have been driven northward by climate change or migrated on farming equipment transported from afar. The team tapped DiTommaso to assist in the effort, since he was a well-established authority on northeast agriculture and weed flora.

There was also a sentimental connection.

“They thought that me being at Cornell, where it all started, would be great,” he said. “And of course, I agreed.”

And so DiTommaso found himself working on the very book that, for decades, people had wrongly credited him with co-authoring.

He and the team reached out to a network of researchers throughout the Northeast for suggestions of weeds to include, as well as color images of their flowers, fruits, collars, sheaths, seeds, stems and the like. For years, the team wrestled with including as much information as possible while also keeping the book a reasonable – and portable – size, for ease of use in the field. There were a lot of difficult choices to make, DiTommaso said, but very few disagreements among the team. (After all, at the end of the day, “you’re fighting over weeds,” he said.)

DiTommaso, for one, was thrilled to include wild parsnip. He’d always been surprised that, as a common weed, it hadn’t garnered a single mention in the first edition. He wasn’t the only person who noticed.

“Especially in our region, come July, you look along the roadsides, and it’s this Queen Anne’s lace-looking thing with yellow flowers,” he said. “It causes photodermatitis, so if you get the sap on your skin on a sunny day, like many of our Department of Transportation guys, or even homeowners who are whipper snipping this stuff, it can really burn. If animals eat it, too, it’s problematic. I was constantly asked, ‘where is it in your book?’ So I couldn’t wait for that species to be in there.”

Other additions include palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri), i.e., pigweed, a most troublesome, summer annual weed often resistant to herbicide, and lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria), a fast-spreading perennial weed of turfgrass and wet areas with showy yellow flowers, which is visible for only a few weeks at the start of spring each year. And of course, the book contains familiar culprits such as swallowwort, kudzu and common ragweed.

While these weeds are clear-cut nuisances for gardeners, DiTommaso hopes “Weeds of the Northeast” also helps cultivate an appreciation for them, too.

“What a weed is really depends on who you’re talking to, right?” DiTommaso said. “I mean, to my dad, dandelions in the lawn are the worst thing that can happen. But I have beekeeper friends who say that’s what the bees are going after and depend on. They love this stuff. So I guess that’s the message, too. An appreciation for a diversity.”

Interest in the book is already sprouting among extension specialists, according to Deborah Grantham, director of the Cornell-based Northeastern Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Center, which has provided more than 50 copies of the new edition to state IPM programs in the northeast region.

For readers who seek more than an identification book and want to take matters, and weeds, into their own hands, DiTommaso recently co-authored a separate book, “Manage Weeds on Your Farm: A Guide to Ecological Strategies,” available free in PDF form.

DiTommaso uses both books in his fall semester Weed Biology and Management course, which is fitting, given that “Weeds of the Northeast” was his go-to text when he was an undergraduate and graduate student in Canada.

“Now everybody I see here, it’s like, oh, yeah, this is my book,” he said. “I’ve signed so many copies. Now I know what it feels like to be like a star.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe