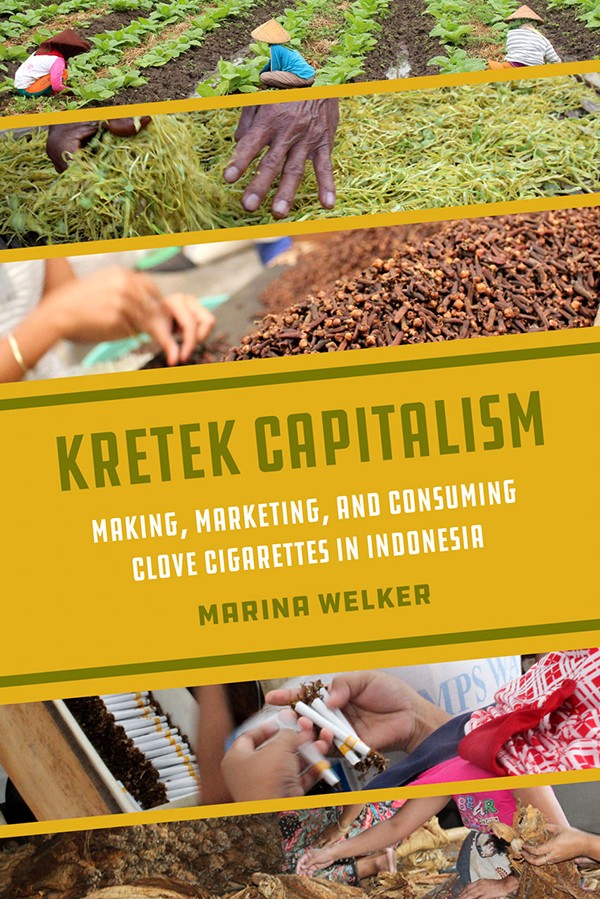

Workers hand roll kretek in a "living factory" at House of Sampoerna, a kretek museum in the East Javanese port city of Surabaya. Kretek museums present the history of the commodity in a nostalgic and flattering light and frame kretek manufacturers as benevolent patrons.

Why kretek – ‘no ordinary cigarette’ – thrives in Indonesia

By James Dean, Cornell Chronicle

During their 10-minute walk to school in Malang, a city in East Java, Indonesia, where Marina Welker was conducting research in 2015-16, her children passed dozens of cigarette advertisements attached to small shops and food stalls – nearly 120 round trip.

It was one measure of smoking’s prevalence across Indonesia, the world’s second-largest cigarette market, where smokers – including two out of three men, but only 5% of women – consume more than 300 billion cigarettes annually. More than a quarter-million Indonesians die of tobacco-related diseases each year.

Though they’re banned in the United States and many other countries, clove-laced tobacco cigarettes called “kretek” (referencing the crackling sound of burning cloves) make up 95% of the Indonesian market.

“Causing harm and death when used as intended, the cigarette is no ordinary commodity,” Welker, associate professor of anthropology in the College of Arts and Sciences, writes in her new, open-access book, “Kretek Capitalism: Making, Marketing, and Consuming Clove Cigarettes in Indonesia.” “The kretek, in turn, is no ordinary cigarette.”

Focusing on Sampoerna, a Philip Morris International subsidiary claiming one-third of the Indonesian cigarette market, the book examines how kretek manufacturers have adopted global tobacco technologies and enlisted Indonesians to labor on their behalf in fields and factories, at retail outlets and social gatherings, and online. Welker discussed her research with the Chronicle.

Question: Kretek produce a distinct sensory experience for many visitors, you write. How so?

Answer: Anyone who has been to Indonesia will be familiar with the smell of clove cigarettes, which is different from “white cigarette” smoke because it has all this spice in it, like incense. The smoke itself is heavier, the way it hangs in the air, which can become very saturated with cigarette smoke. When tobacco control groups measure the air quality at indoor and outdoor events, they find that it’s quite toxic.

Q. And visually, you describe the blitz of advertising many residents encounter, including your children as they walked to and from school.

A. These were just ordinary streets, not busy thoroughfares. During a similar walk to school in the U.S., my kids didn’t see a single cigarette ad. There’s an injustice to it. It’s not as if we don’t have any cigarette advertisements in the U.S. Here they’re targeted more toward lower-income and people of color. But neither is it that level of saturation. One of the things I’m thinking about in the book is all the labor that it takes and all the relationship-building that’s involved in creating an environment so saturated with advertising.

Q. What makes Indonesia and kretek different from other cigarette markets?

A. It’s a story of both distinctiveness and similarities. There’s a distinctiveness to the cigarette industry, of course, in that it is a killer commodity. Then with kretek containing cloves, “kretek nationalist” organizations claim that this indigenous spice, combined with the New World crop of tobacco, makes a special commodity that is vital to cultural heritage, to thousands of farmers and factory workers, and to local economies. Museums present the industry as something indigenous, romanticizing kretek in a positive, artisanal light – similar to its portrayal in the recent Netflix series “Cigarette Girl.” Commodity nationalists don’t acknowledge how the industry has adopted Big Tobacco’s global strategies and technologies – from mechanization and advertising to misleading claims about filtered, “mild” and “light” cigarettes being safer, to using social media and influencers to attract young smokers.

Q. Why are kretek and smoking so popular in Indonesia?

A. The industry has been so successful in ensuring a lax regulatory environment. Cigarette packages do have graphic, gory warning labels. But the most central thing has been maintaining an environment in which you can have such rampant advertising. Politicians – who are predominantly male, with smokers being predominantly male – often pick up kretek nationalist narratives about a distinctive national commodity that employs so many people and that would suffer from new taxes or restrictions. My book focuses on the industry’s success in enrolling many kinds of labor to ensure its own success.

Q. How important a role have Phillip Morris and other international firms played in the industry’s success?

A. Indonesia was the only Southeast Asian country not to ratify the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2003, and so they moved in. While they were preaching a futuristic “smoke-free” vision in predominantly white and higher-income Western countries, they were expanding conventional combustible cigarette operations in places like Indonesia.

Q. Some have described visiting Indonesia as like going back in time, resembling Western countries decades ago in terms of smoking. Do you agree?

A. The time travel trope is problematic and offensive in many ways. Indonesia is not frozen in the 1950s. It has pictorial health warning labels that the U.S. doesn’t have, so is arguably ahead in that regard. That discourse of backwardness and shaming creates space for kretek nationalist narratives to say, “We’re not behind, we have this special commodity, and we don’t need your neocolonial tobacco control.”

Q. What could help reduce smoking there?

A. Indonesia does have a tobacco control movement, but it’s very thin on the ground compared to the ubiquity and economic power of the cigarette industry. It’s a predominantly Muslim country, and there has been some strong articulation but limited uptake of the idea that smoking and cigarettes are “haram,” or prohibited, so that’s one place with potential. More recognition is needed of gender violence in the industry. The masculinity of boys and men is questioned if they don’t smoke, and women suffer both the bodily toll of ambient smoke as well as smoking’s toll on household economies, which is enormous. And then also thinking about class injustice. As in the U.S., poor people who can least afford the consequences are more likely to smoke than higher-income Indonesians. The picture is far less rosy than industry proponents and kretek nationalists make it out to be.

Media Contact

Adam Allington

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe