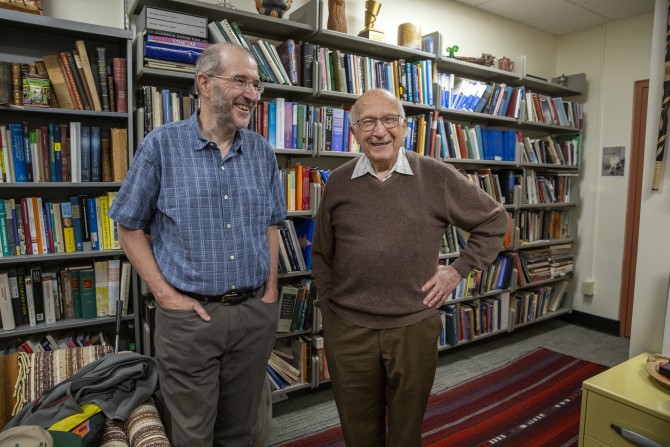

Roald Hoffmann, Frank H. T. Rhodes Professor, Emeritus in the department of chemistry and chemical biology in the College of Arts & Sciences left, stands with alum Jeff Fearn '82, right. Hoffmann and Fearn connected for the first time in more than 40 years through the Center for Teaching Innovation's Thank a Professor Program.

News directly from Cornell's colleges and centers

CTI's Thank a Professor program connects alum, professor 40 years later

By Carolyn Keller

There’s no due date on gratitude – even if four decades have passed.

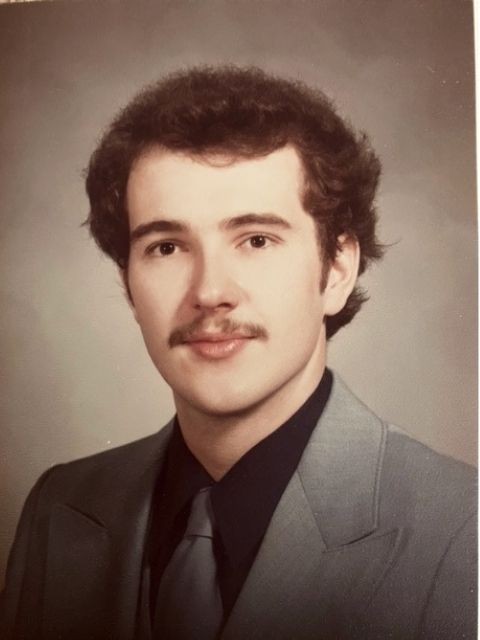

Jeff Fearn ’82 always meant to thank Roald Hoffmann, Frank H. T. Rhodes Professor, Emeritus in the department of chemistry and chemical biology in the College of Arts & Sciences, for the impact his teaching had on his life and career.

He just didn’t expect the opportunity to arrive four decades later, in a weekly email that Willard Straight Hall sends to Cornell’s undergraduate population.

One of those emails mentioned the Center for Teaching Innovation’s Thank a Professor program. The program is offered in the waning weeks of each fall and spring semester, and provides an invitation, via a Google form, for students to write anonymous notes of gratitude to professors who have impacted their learning. CTI then delivers the messages in early January and June, after grades for the preceding semester have been submitted.

Fearn doesn’t remember subscribing to the Willard Straight newsletter, but when he saw the Thank a Professor program advertised there, he knew his opportunity had arrived. While the Thank a Professor program is typically aimed at current undergraduate and graduate students, there’s nothing necessarily stopping alumni from writing to their former professors, too.

“(Hoffmann) was the best college teacher I’ve ever had,” Fearn said. “I looked at the email and thought, well, don’t let it just sit in your inbox gathering dust.”

And so he sat down to write:

“Dear Dr. Hoffmann, this thanks is a bit late, 40+ years in fact. I took PChem when you taught the course (in the '79-'80 year I believe) … I credit your approach and your class for turning around my academic career and continuing on with my successful scientific endeavors. I have strived to follow the same philosophy during my career, whether helping others learn the ropes or solving problems. Thank you very much.”

Fearn included his name and contact information in his message. Then he clicked submit.

In 1979, Fearn had enrolled in Hoffmann’s physical chemistry course in the fall semester of his sophomore year as a biochemistry major in the College of Agricultural & Life Sciences. The course, which is taught by a rotating roster of faculty in chemistry, was required for Fearn’s major, and Hoffmann happened to be teaching it the semester he enrolled.

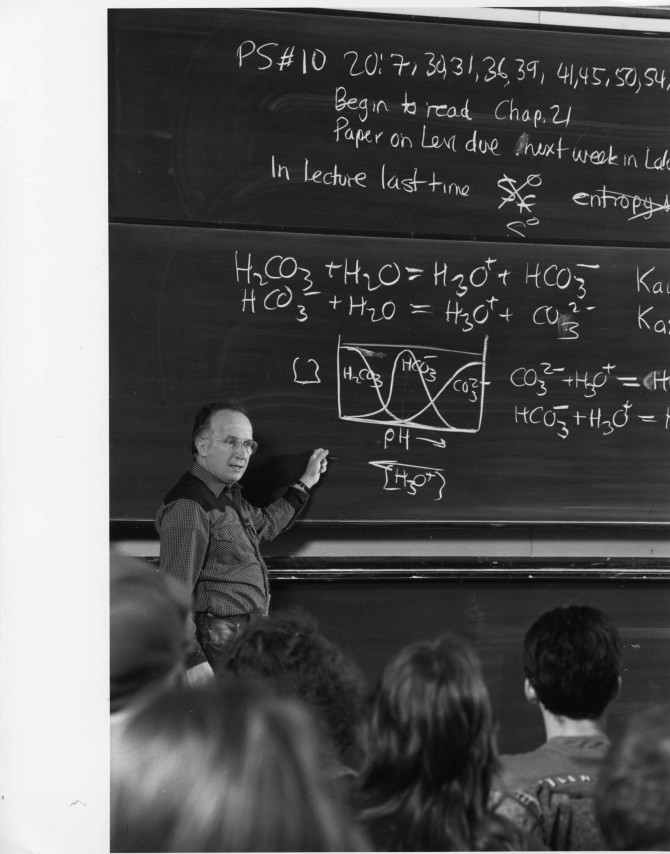

It was Hoffmann’s demeanor in the medium sized lecture hall that first caught Fearn’s attention. In a course whose size ranged from 60 to 100 students, Fearn said Hoffmann had the ability to make students feel he was having an individual conversation.

“It wasn’t like ‘I’m the professor,’” Fearn said. “It seemed like he was talking to you one on one. Even his response back (to Fearn’s Thank a Professor note) was the same way: ‘so nice to hear from you.’”

But it was Hoffmann’s approach to exams that made the biggest impact on Fearn’s life – and future teaching career.

“That’s always been my downfall – I don’t memorize easily,” Fearn said. “I’d say why memorize it when you can look it up?”

Fearn’s struggles with memorization made exams even higher stress situations than usual. But when it came to exams, Hoffmann took a different approach, from the exam room’s ambiance to the exam itself.

To create a calmer space, Hoffmann would lower the exam room’s lights a bit, and have classical music playing. He also didn’t require his students to memorize necessary formulas and let students bring a “cheat sheet” with formulas they could reference – or he provided the formulas himself. Finally, out of the six total exams that they took, students were allowed to drop their two lowest scores, ensuring that one bad test wouldn’t tank their grade.

These strategies, which had such an impact on Fearn, were very much intentional. While Hoffmann is a known researcher – he won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1981 for his theoretical work on the course of chemical reactions – he’s also clearly a teacher at heart, speaking with affection for his students and teaching, and with intention regarding his pedagogical strategies and approaches.

For Hoffmann, the first task in teaching is always to create a connection between the professor and students.

“I want to get it into students’ head that I’m a human being – that’s the contact point,” Hoffmann said. “The emotional contact is very important for the learning process. If the student knows that you care for them and care that they learn, they will respond very well.”

As Fearn suspected, Hoffmann didn’t just “seem” to be speaking to students one on one – he was actually doing that. He always tried to speak to individual people when giving a lecture, switching his gaze in the classroom so as not to make any one individual uncomfortable. He also recognized that chemistry can be a difficult subject to learn and used his own experience to further foster connection.

“I try to tell the students that (chemistry) is difficult for me, so I understand that it’s difficult for them,” Hoffmann said. “I try to get them to enter my way of thinking as I prepare a test, just as I try to enter theirs as I prepare to teach. They should imagine, ‘The professor has taught us something. He wants to test our understanding. Now how would I (the student) do that?’”

For Hoffmann, it’s not about memorizing the formula. “That’s not where understanding resides, he said. “The test of understanding is using the concept in a different setting, all the settings where it arises.

Also – that cheat sheet wasn’t just a cheat sheet. It’s true that Hoffmann allowed students to take an 8.5 inch by 11 inch sheet of paper into the exam room, and “they can put anything they want on it. The cheat sheet strategy reduced anxiety. And in preparing what to put on the sheet, the students got to concentrate on essentials.”

In other words, the use of a cheat sheet was a deliberate move on Hoffmann’s part to encourage deeper learning, and there were additional strategies attached.

“I’d encourage them to compare the sheets and sometimes I’d give an award for the best sheet. It was, of course, a way of encouraging them to study, to give themselves exams. It would start a discussion between them,” Hoffmann said.

For Hoffmann, the keys to teaching are “enjoying it, yet taking it seriously, all the time with as great empathy as one could muster. It is also important that younger faculty see that the research stars want to teach” In time, the faculty learns what Hoffmann says he learned – that “in teaching others, we teach ourselves. Understanding and explanation are two sides of the same coin.”

That spirit can be absorbed by students as well. While Fearn has spent much of his career in the science and technology sector, he also taught for several years, as a TA at Cornell, as a long-term science and math substitute position at a school in Lake Placid, and a teacher at a school for youth overcoming disadvantages, some of whom needed extra encouragement.

When he found himself in the front of the classroom – and especially when he was giving tests – he thought of Hoffmann, and how he too could use strategies to help his students truly learn.

For example, after a test, Fearn opened a short window of time where students could come in with their notebook, find the right answer for questions they’d missed on the test, and get half-credit for the question.

“For me, that was more learning,” Fearn said. “That was my way of trying to interpret how (Hoffmann) would do things.”

Now retired, Hoffmann can still be found in his office for a few hours, nearly every day of the week. When he talks about his students and his years in the classroom, his voice is warm and fond.

“I miss the teaching. I am very proud of having been a teacher – I hope that comes across. Therefore, something like what I got from Jeff was very sweet. When (students) say something that they remember, it’s very nice for us,” Hoffmann said.

Fearn, meanwhile, was happy for the chance to connect again with his former professor.

“Once I saw the Thank a Professor link, I knew I had to do it,” Fearn said. “It's never too late to thank, or think of, anyone.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe