When the pandemic shuttered school buildings, units across Cornell’s campuses swung into action to help support education for the millions of suddenly homebound K-12 students around the world.

Cornell’s K-12 programs foster creativity, community

By Melanie Lefkowitz

The packages came Mondays and Thursdays.

“Eleven-thirty rolls around and then I hear ‘knock, knock, knock’ on my door and there’s a box of really good food,” said Camryn Ames, a rising junior at Elmira High School in Elmira, New York, and a participant in Cornell’s Upward Bound program. The federally funded program helps prepare students for college with support including weekly prep classes and a six-week summer session on Cornell’s campus.

The boxes contained family-style meals prepared and packed by Cornell Dining – enough for siblings or parents to share. They were part of Upward Bound’s efforts to make this summer’s all-virtual session – with students alone at their screens rather than living together in residence halls – engaging, rewarding and even a little bit festive.

“I was dreading this summer because we were going to have to do everything online, but they’re doing it flawlessly,” Ames said. “We’ve all suffered socially when it came to the pandemic. So it’s been very helpful to be associating with people and also have the feeling that I’m completing my goals with the summer classes. And even though we’re on the computer all the time, it’s still fun.”

When the pandemic abruptly shuttered school buildings across the nation in March, units across Cornell’s campuses swung into action.

Some, like the Public Service Center, which is home to Upward Bound, were already working directly with K-12 students; others, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell Botanic Gardens and Paleontological Research Institution, curated resources that parents or teachers could use to engage millions of suddenly homebound kids around the world.

Educators from Cornell Tech, who had been training New York City teachers to incorporate computational thinking into their classrooms, refused to abandon an ambitious robotics project. And Cornell Adult University, which usually welcomes around 350 young people to campus for summer programs, reached nearly 1,500 students in more than 20 countries through a newly free and open slate of online courses.

“Instead of expecting them to come to us,” said Liz Millhollen, Cornell Upward Bound’s associate director, “we came to them.”

Keeping kids close, at a distance

At Upward Bound, the urgency was high – and so were the stakes. The pandemic created huge challenges for these at-risk students, many of whom lived in far-flung rural areas in upstate New York. With schools closed, some students were now almost completely isolated. Some were stuck in unsafe home situations; others lacked internet connections.

“The first thing – day 1 – was that we didn’t want to have technology barriers. We had to figure out: Who’s going to get to keep their school Chromebook? Could they even get on Google Classroom? Were they going to have to participate on their phones?” Millhollen said. “We were on the road, we were texting, calling and meeting folks face to face. So we definitely know about the challenges, and why some students don’t show up. We’re doing our best to support their safety.”

An all-online format was an imperfect substitute for a regimen that normally relies on building relationships through in-person tutoring, counseling, workshops, classes, conversations, social events and trips. But instructors supplemented it as best they could, starting with socially distanced driveway visits to make sure students had what they needed.

Deliveries included workbooks, textbooks and boxes of supplies for lab experiments in physics and chemistry. Soon after schools closed, staff mailed packages to the students with Upward Bound stickers, moleskin notebooks and fancy pens, to use during journaling prompts.

“The appreciation and the love we got back for that was huge,” Millhollen said. “Those things signaled to the students ‘Even though a lot of things are changing in your life, Upward Bound… is not changing our dedication to you and your success.’”

Usually, the roughly 100 students in Upward Bound spend around 12 hours a day at classes and events during their Cornell summer sessions. This year, classes were condensed to around two hours a day, because students couldn’t realistically spend all day on Zoom. In the afternoons and evenings, online events such as talent shows and family game nights helped participants remain enthusiastic and close-knit.

“It seems like we’re so distant, but on Zoom, we’re very close,” said Ames, whose Upward Bound experience helped him find his interest in graphic design, and who plans to apply to multiple colleges, including Cornell. “It’s just a beautiful community that we’ve all come together and formed.”

Free, open and online

Traditionally, Cornell Adult University’s (CAU) youth classes were like camps for the children of alumni participating in on-campus courses. In recent years these youth programs have grown to include courses in science, law and the arts, drawing students from the Ithaca region and beyond.

This year, with on-campus programs shut down, CAU did something different: It made these virtual classes available for free. Rather than creating interactive classes of 15-20 students each, as they originally intended, staff decided to leave enrollment uncapped, to accommodate as many students as possible.

“We wanted to touch on a variety of topics for teen audiences, from engineering and veterinary science, which are really in demand, to creative writing, for kids who want to take the time to compose,” said Lora Gruber-Hine, CAU director. “And we had a tremendous response.”

For the instructors, many of whom are undergraduates, the shift to online teaching was a challenge. Caroline Hinrichs ’22, a nutritional science major in the College of Human Ecology, originally took a job with CAU as a day camp counselor, but wound up teaching an online class in polymer science.

“It’s been kind of a wild ride – really cool and really rewarding,” Hinrichs said.

Since she couldn’t display physical 3D models in person, she found websites that illustrate 3D molecule modeling, and recorded science experiments on video in her backyard to show the students.

“I’ve gotten better as I’ve taught more classes,” she said. “I’ve learned to be more responsive to the questions and the chat, so it’s not just a lecture, with information going one way. It’s a back-and-forth flow between us.”

Students in the online classes came from all over the world – from Mexico to Romania to Bahrain – so program directors sought to connect them virtually to the Cornell campus. They created weekly challenges sponsored by the Big Red Bear, such as asking participants to re-create McGraw Tower with any materials they chose, and entries included a three-layer cake and a tower built of Legos. The bear was filmed visiting various spots on campus, including the College of Veterinary Medicine, where a student gave him a physical exam.

“We had very little experience delivering any content online,” Gruber-Hine said. “Everyone was growing into this virtual platform. We viewed this as a gesture of goodwill, an experiment to see what we were capable of doing, and a thank-you to the community that has been struggling and trying to find ways to engage.”

Building robots and grit

Before the pandemic, Kelly Powers and Niti Parikh, teachers in residence with the K-12 Initiative at Cornell Tech, had an idea: Teach elementary students how to create animal-inspired robots by observing nature.

“Some people absolutely thought, ‘You’re crazy to try to do this with third grade.’ But both Niti and I come from a background where if you engage students really deeply, they have some agency,” Powers said. “Robotics engineers do get their inspiration from how animals move. How cool is that? And kids understand animals, kids love animals. So it was just a wonderful marriage of what kids already love and engineering practices.”

But when the pandemic struck, it seemed impossible to follow through.

“It was pretty ambitious to begin with. Once we went into lockdown, I was sure this idea was going to go by the wayside,” said Diane Levitt, senior director of K-12 education at Cornell Tech. “But they were super committed to it.”

The difficulty, Powers said, was part of the point. “When you’re making, you’re going to fail a lot,” she said. “We needed the community, that culture of collaboration, to build each other’s perseverance and grit.”

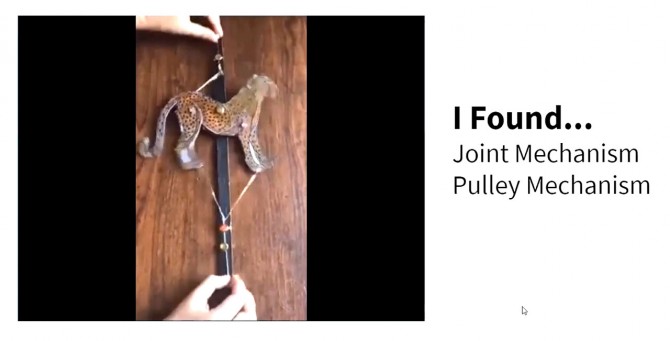

Parikh and Powers convinced the teacher of one third-grade class at PS 86 in the Bronx to devote an hour a week to their project – it wound up occupying students for far longer. Deciding that having students observe the animals around them – squirrels, birds and household pets – would be too limiting, they showed them videos of animals in nature. Step by step, they taught the students how to use household items to create mechanisms such as belts and pulleys.

“We introduced them to cams, which are the wheels on the axis that make things go up and down or swivel around. How does that motion happen? What are the forces?” said Parikh, who is also creative lead for Cornell Tech’s MakerLAB. “Seeing the joy in their eyes when we would do this, in making-sessions in groups of four or five students, was amazing. The students stayed for hours, overlapping with other students’ time, to make sure it happened.”

Materials were a major challenge. Even the relatively basic items they asked students to supply – toilet paper rolls, for instance – became hard to find, because of the shortages in the pandemic’s early weeks.

At first, Parikh and Powers encouraged students to build “inspiration boxes” with materials they had on hand – cereal boxes, paper clips – and the students drew and prototyped with what they had. As the weeks progressed, the instructors realized that to ensure students had what they needed, without making it obvious which students had fewer resources, they needed to purchase supplies for them. Parikh and Powers created boxes for each student, with items such as hole punchers, fasteners, zip ties, rubber bands and balloons, and sent them to students’ homes.

“Then they all had a very similar palate of materials to work from, and they could add their creativity to it,” Parikh said. “And I think it was a good encouragement to them, that we believe in them.”

Unprompted, students sent the teachers photos of themselves with their supplies. They also recorded videos of their robots, which included a cheetah puppet that uses joint and pulley mechanisms to move its legs, an egg that hatches with the aid of a cam and joint mechanism, and a frog that uses air pressure from a bottle to inflate its vocal sac.

“Honestly, I have to say, I’ve never seen anything like it. I’ve never been so happy to be wrong about anything in my life,” Levitt said. “Kids want to create – they’re wired to create. And when you give them permission, when you treat them like artists and creators and designers and engineers, that’s how they behave.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe